Does training LLMs with RL improve their ability to reason?

Or, does it draw from a fixed reservoir of reasoning ability that's already in the base model?

Recently I got into an X argument with doomslide about whether we are any closer to AGI since the release of ChatGPT o1. I considered this a completely absurd assertion, and started by accusing the other poster of deliberate rage-baiting. (Not my best moment, but in fairness their posts were comparing AI evaluations to monkeys with sticks). I think the whole discussion was fine, I managed to understand their claims and we got to a point of disagreement: whether lowering the costs of existing capabilities (that is, Sonnet 4.5 being able to code the same things as Sonnet 3.5, but more reliably and cheaply) would also result in increasing capabilities. I took the yes side, and the frog took the no side.

Because of this argument, I got a chance to dig into some papers representing its position. First is “Does RL Really Incentivize Reasoning Capacity in LLMs Beyond the Base Model?” by Yue, Chen et al. 2025, which argues that models trained with RL with verified rewards are getting more sample-efficient at low amounts of samples, but lose reasoning capacity compared to base models and eventually the latter surpass them. The second paper is “Scalable Synthesis of Theorem Proving Challenges in Formal-Informal Pairs” by Zhang, Jiang, Liu et al. 2025, which evaluates a range of models on synthesized problems about Busy Beaver behavior, and shows that small specialized theorem-proving models are really bad, and mainstream models surpass them (and are also not great).

From these papers I think my original position was totally wrong, and doomslide was correct: cheapening existing capabilities does not necessarily, or in practice, make the models more capable overall. My belief now is that the original scaling hypothesis is undefeated (larger models are better) but the current trend of RL scaling (as opposed to parameter scaling) might not get us there.

Does RL really incentivize reasoning capacity?

The usual story of LLMs trained with RLVR (RL with verifiable rewards, i.e. programming and math environments) is that they learn to reason better from those environments. Certainly this matches previous uses of RL in AI, where over training models are able to learn novel strategies. This is how AlphaGo beat Lee Sedol: by playing itself and learning with reinforcement learning.

When comparing which of two LLMs can answer a question, we typically ask each of them the question once and check if they got it right. If we want to be more precise or avoid getting fooled by randomness, we try the LLMs some number of times (say, K times) and report their averages. Popular benchmarks like MMLU and GPQA typically ask each question once and report the average over many questions, which also stabilizes the results.

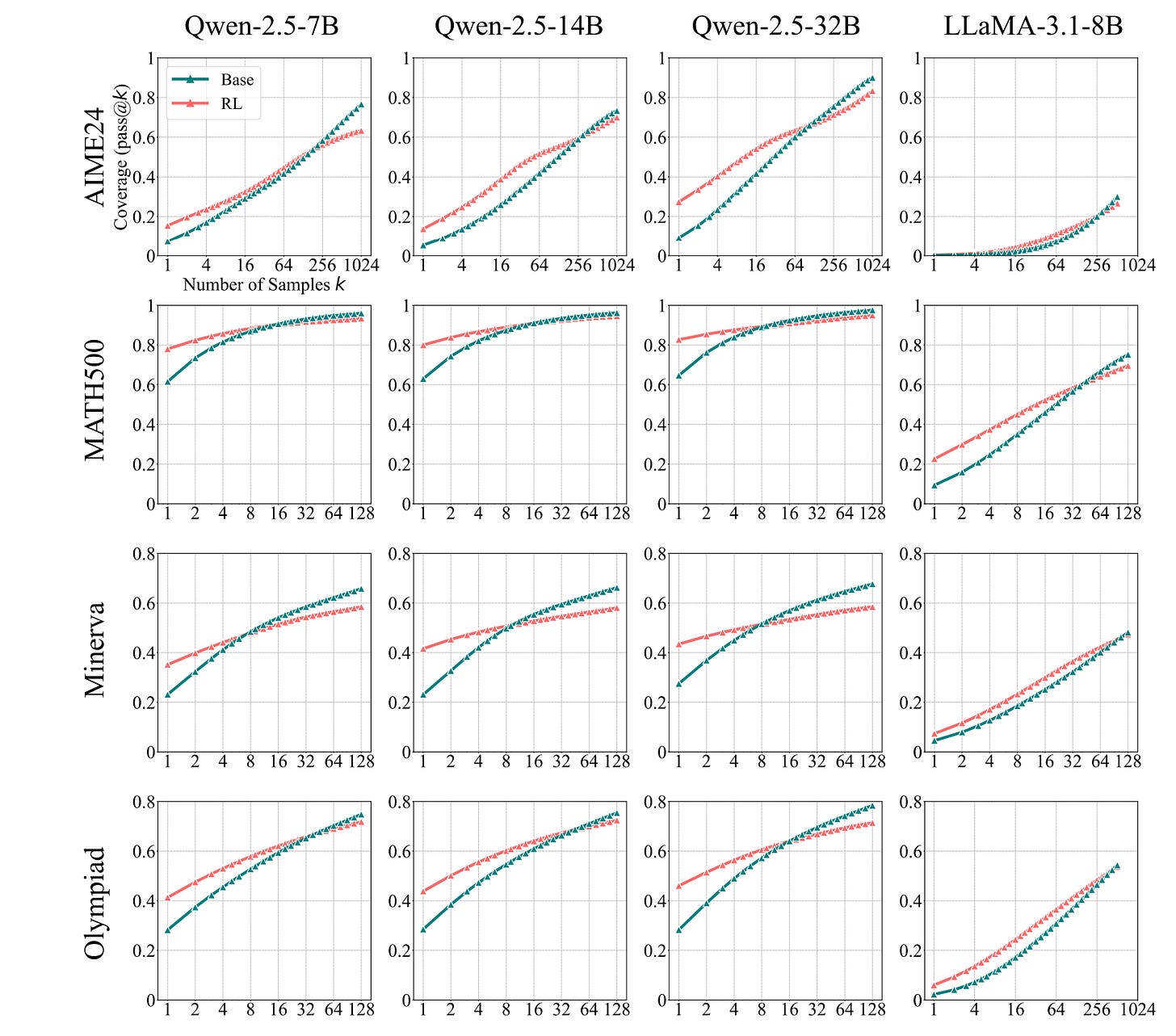

Yue, Chen et al. have a different hypothesis: what if the base model already knows all the reasoning trajectories, and all RL does is increase the frequency of reasoning or the frequency of the trajectory that is likely to work? To test this, Yue, Chen et al. use pass@K: let’s give the LLM a total of K attempts to answer the question, and if any of them succeed, mark the question as answering correctly. They report the proportion of correct questions in the data set.

If the base model already knows how to reason and all RL is doing is increasing the frequency of it, then we should expect the RL and base models’ performance to converge. As we try more and more times, eventually either both models will answer the question (if the base model knew how to), or no model will answer it (if the base model did not know how to.) [Strictly speaking this is always true, monkeys with typewriters do type out Shakespeare or an answer to the question. However in reality we’ll use K up to 200 or so, which is a miniscule amount of attempts for a monkey, so the base model has to be pretty good at reasoning already to pass.]

If the RL model genuinely learns new reasoning skills, over many questions the pass@K performance of RL will remain higher than the performance of the base model. As we increase K, the base model answers more and more of the easy questions, so its performance improves. But the RL model’s performance also answers more and more difficult questions. The performance of both increases in tandem with larger K.

What actually happened is neither of these two things. For large enough K, the base model does better than the RL model. (!!!)

Notice for how all these lines, the performance of the RL model (orange) base model (teal) eventually cross over, at some point between K=16 and K=400 samples.

This is extremely weird! It implies that the RL model is able to answer more reliably for easy questions, but actually loses its reasoning capability for difficult questions. On the difficult questions, when you give both models enough samples, the base model does better. This paper convinced me that my original assertion was wrong: cheaper capabilities on RL models (because they e.g. need fewer samples) does not necessarily result in models with higher overall capabilities.

If this picture is correct, scaling RLVR compute has not yielded increasing capabilities. There are certainly caveats to the evaluation in this paper: because of the lack of a public API for the base DeepSeek model, the authors did not do this comparison on large, frontier reasoning models. [Though note that Kimi K2 has 32B activated parameters per forward pass, which is the same size as the Qwen-2.5-32B model here. Kimi has 1 trillion parameters total because of the ‘mixture of experts’ which chooses which set of 32B parameters to use on each particular token.]

The paper does note that distilling from a bigger model does qualitatively improve a small model’s reasoning performance, in a way which has no crossover.

Does RL-training LLMs improve their ability to prove theorems?

We now turn to the second paper, “Scalable Synthesis of Theorem Proving Challenges in Formal-Informal Pairs” by Zhang, Jiang, Liu et al. 2025. They synthesize a bunch of theorems to prove, about the behavior of Busy Beaver Turing machines, with two statements: a formal one in Lean, and an informal one in a Markdown document.

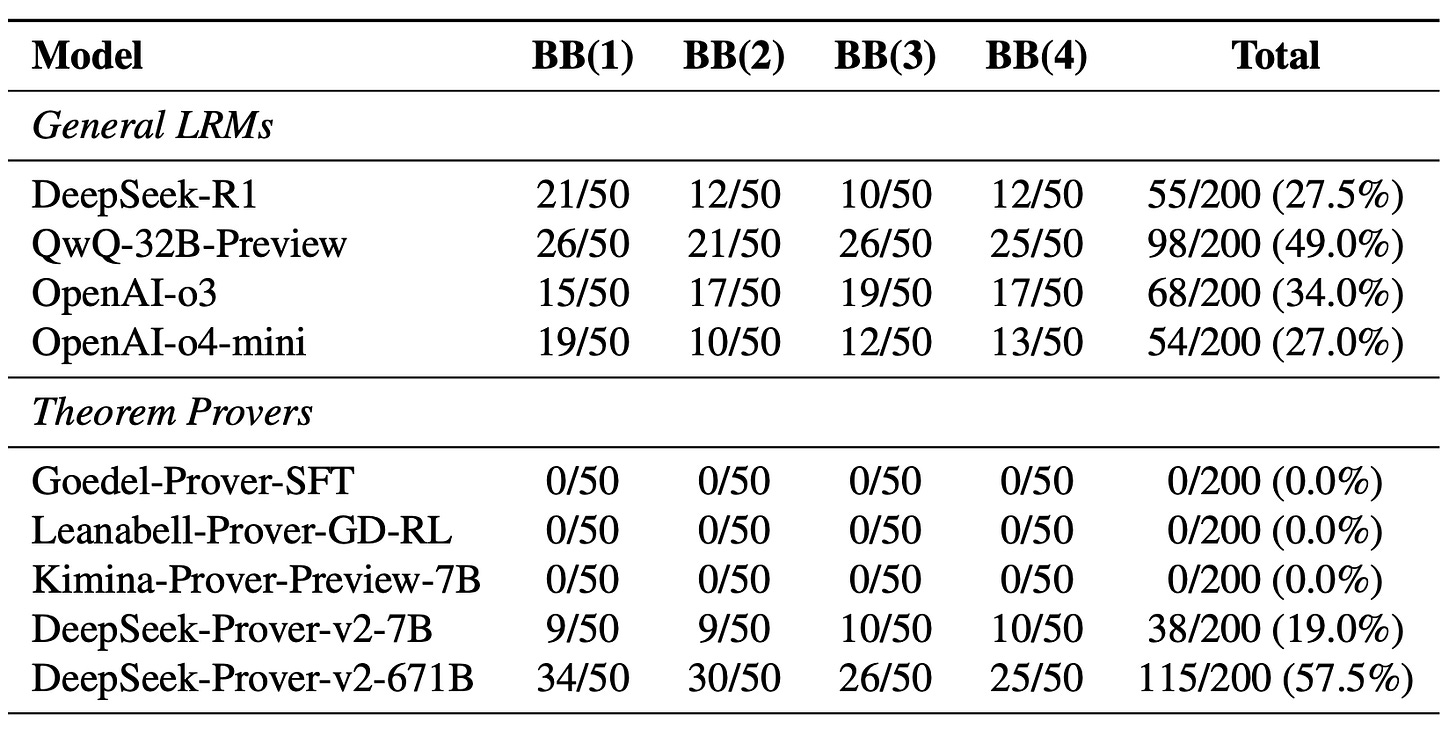

The key thing to look at is this results table, which is also pass@16 (an answered is marked correct if it is correct in any one of 16 attempts):

The main pattern I can see is that model size explains all the performance. Small, specialized theorem-proving models (Goedel, Leanabell, Kimina and DeepSeek-Prover-v2-7B) do extremely badly: the first three models get absolutely zero answers correct (even with 16 attempts), and only the DeepSeek 7B model gets anything right. Slightly higher up are the general-purpose models: ChatGPT o4-mini and o3 (unknown size, but probably similar to or larger than R1), DeepSeek R1 671B, and Qwen with Questions (QwQ) 32B.

The best model is the DeepSeek-Prover 671B model, which is exactly the same size as DeepSeek R1 but also has had RL training for proofs. By comparison to DeepSeek-R1, we can see that the RL training helps, but it’s not much better than the QwQ-32B model (49% vs 57.5%) even though it has had specialized training

Combining this with the previous paper, k=16 is on the lower end of where we expect crossover of base and RL models, so that RL helps here does not contradict the previous paper.

My tentative conclusion from this is that newer models are better, but only because of scale.

Conclusion

Perhaps RL actually doesn’t improve the model’s intelligence, and only changes how often models they get things right on the first try! I certainly wouldn’t have noticed anything differently if this was the case, I don’t tend to prompt models 100 times to do the same task. I also wouldn’t be surprised if OpenAI and Deepmind when doing their massive IMO runs hadn’t noticed anything: it’s unlikely that they gave the computational budget of millions of $ to base models.

Of course this still means that RL-training the models is economically useful: ideally we would get the answer from just one prompt. However, it does mean that perhaps the ever-increasing benchmarks and models aren’t coming up with any “new” intelligence, they’re just mining what’s already in the base model (unhobbling). This suggests that it will peter out at some point, and we’ll need to go back to very expensive pre-training scaling.

Overall I think this lengthens my timelines and lowers my opinion of how good we are at evaluating model performance. Now that the problem has been pointed out, I expect it to go away with better RL algorithms.

curious about performance on ‘reasoning questions that might be in the training set’ vs ‘generalization to reasoning questions we’re pretty sure aren’t in the training set’—might go through these papers looking for how training-set-heavy their questions were later

https://arxiv.org/pdf/2510.14901

shocked at the omission of this paper